How Grief and Anger Turned Into Action

Natasha Christopher remembers everything that happened on the night of June 27, 2012.

She remembers sharing the bedroom with her five-year-old, who was having a nightmare. She remembers her boyfriend waking her up and telling her that her eldest son had been shot. She remembers looking at the clock, its hands pointing to midnight.

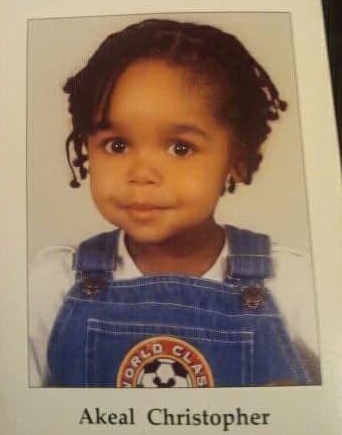

That Wednesday night, Christopher’s 14-year-old son, Akeal, took a bullet in the back of his skull on a residential sidewalk in Bushwick. He was taken to Brookdale Hospital, a 20-minute drive away, where Christopher arrived with her two younger sons, Rashawn, ten, and Christopher, five.

She remembers that her relatives stood at one side of the waiting room; Akeal’s father’s family on the other. “Where is my son?” she demanded, staring into sullen faces and downturned eyes. Nobody responded.

Christopher pushed forward, walking past the emergency room doors, and felt her muscles tense at the sight of blood on the floor. The alarms rang “Code Blue,” a signal she didn’t understand.

Then she noticed the drapes in a nearby room swing open, and behind it Akeal lay bleeding on a gurney. A doctor was pumping his chest. A nurse talked about stapling his head. Someone shouted, “Get her out of here!”

Christopher ran back outside and pounded on her son’s father. “What the hell happened to my son?” She screamed.

Then she passed out.

***

Everything changed. The night Akeal died set in motion years of grief for Natasha Christopher, sometimes morphing into anger and then into action. She still doesn’t know exactly what happened to her son that June night on the corner of Cornelia Street and Evergreen Avenue.

A vivacious woman with a side-shave of cobalt hair and a Caribbean accent, Christopher was born in the island of Trinidad and emigrated to the United States in the early 1990s with her two brothers; her mother, formerly a nurse; and her father, who became a security guard at the World Trade Center. Her family instilled in her the values of community, respect, and success, which she tried to pass on to her children after they were born.

Life was good for Christopher in the months before the shooting. The eldest of her three sons, Akeal was a freshman in Transit Tech High School, hoping to fulfill his childhood dream of becoming an engineer in the rapid transit industry. The family had recently moved to Queens from Bushwick, and Akeal was ready to spend the summer at his father’s home in Crown Heights, as he usually did. On June 24, his grandfather picked him up, and Christopher began preparing for her middle son Rashawn’s orientation, following his acceptance at the Philippa Schuyler School for the Gifted and Talented in Bushwick.

Three days later, Akeal and his 13-year-old cousin were invited to a high school graduation party at a friend’s house in Bushwick. Seven boys, including the two, were walking the streets at 11 p.m. when a gunman fired four shots. Akeal was the only one who went down.

At the hospital, Christopher saw the extent of physical damage a single bullet had done to her son. His head was swollen and his tongue stuck out of his mouth. She prayed and prayed that her boy would live. His doctor, Mary Baldauf, said she would do everything possible to save Akeal. But Christopher was also realistic.

“For 14 days, I got a blanket and a sheet, and I laid on that floor beside my son,” she said, “watching my son, every single day, die before my eyes.” Akeal’s heart stopped the morning of July 10, on what would have been his 15th birthday.

Akeal Christopher (Samantha McDonald)

Christopher brought Rashawn and Christopher to Akeal’s bedside to say goodbye, and began to plan the funeral. At the same time, she was in contact with several detectives, who didn’t have any leads about the unknown assailant. Witnesses gave conflicting accounts, and the children who were with Akeal that night refused to talk.

To date, the shooter remains at large, but Christopher continues to investigate the events surrounding Akeal’s death. “I’m going to find out what happened to my son,” she said. “I will keep doing it until the day I die.”

In October, just three months after the shooting, Christopher went back to the site to seek answers from residents. The visit prompted her to become more active in promoting gun safety in the community. In the following months, she joined Moms Demand Action, a nonprofit organization for gun control. Now every year on his death anniversary she stages a peace walk and a candlelight vigil at the intersection.

“I had to turn my pain and anger into action,” she said. “The one thing that has caused me so much pain has now become my passion. Losing my son destroyed me, but my life has purpose.”

***

At Highland Park, where Elton Street cuts into Jamaica Avenue, Christopher waited for her now 9-year-old son Christopher (his first and last names are the same) before crossing the road. No more than 20 minutes later, after she sat on a bench diagonal from the basketball court where Christopher played, droplets of rain started falling.

“Come, Christopher,” she beckoned. He followed, dribbling his basketball.

While looking for a cafe or restaurant where they could wait for the rain to pass, Christopher remarked on the prevalence of liquor stores and cigarette shops that dotted the streets in this part of Brooklyn. “They don’t even put the community’s needs first; you don’t see anything out here for the young kids,” she said. She has become convinced of the influence of environment on people’s actions. “You have to invest in your future.”

Since her children have grown old enough to walk the streets alone, Christopher has been careful to teach them the general rules for safety: Don’t talk to strangers. Come home before sundown. Be polite to elders, especially the police. “We already know how young black men and Hispanics are stereotyped,” she said. “It’s either you’re gonna end up in jail or you’re gonna end up dead. And I wanted that not to be my son.”

Yet she never could have predicted the events that led up to Akeal’s death. The boy’s father had refused to tell that he would be attending the party that night, afraid that if he asked Christopher about it, she would say no. Then all it took was one man and an illegal gun to end the life of a boy who had always respected the law.

Now Christopher advocates for stop-and-frisk, which she believes could save the lives of many black children, including her son’s. The controversial policy began as part of former mayor Rudy Giuliani’s plan in the 1990s to combat crime in the city and lessen the number of guns on streets. But that didn’t sit right with many people in black communities—the usual target of stop-and-frisk, with 54 percent of the stops last year. In fact, stop-and-frisk was ruled unconstitutional in 2013. Many black New York City residents were relieved, but Christopher argues that this exposed the city to more crime. According to NYPD crime data, there were 7,135 stops in the first quarter of 2015, down from 14,261 at the same time in 2014.

Akeal Christopher (Samantha McDonald)

After losing her son, Christopher became more involved in the gun safety community, too. Among other things, she encourages women to speak about their experiences with gun violence, particularly those who fear that their voices won’t be heard over the cacophony of politicians and community members who, in Christopher’s view, have done little to nothing for security in her neighborhood.

“We all grieve differently, so what I try to teach them is that if they don’t fight for their child, nobody will,” she said. “If I tell my story and save one person’s life, then I know I’m honoring my son every single day.”

***

Sunlight shone through the windows of the pizza parlor where they finished lunch. Christopher’s son grabbed his basketball, and together they headed back to the park so he could continue his shooting session, and and so she could share a moment with Akeal, whose picture rested inside a faux brass frame she grabbed from her purse.

“That’s my baby,” she said. “It’s just so sad to see that smile.”

Because Brooklyn was too expensive, Christopher bought a plot in New Jersey for her son’s burial. Without a car, she can only visit as many times as her brother can drive her to the cemetery. On weeks when she can’t travel, she walks over to the park and sits down with his framed picture propped on the bench next to her.

“I come here, I sit here for hours upon hours, and I watch some of these young boys. I’m like, ‘Oh my god, I’ll never see my son again,’” she said. “When I go there and see his headstone, I still can’t believe this is my life.

“I do things to keep me motivated, but at the end of the day, we all sit down and have that quiet time,” she said. “Everyone has gone on with their lives as if nothing happened, but for me everything has changed.”

After about 20 minutes, Christopher packs the frame with Akeal’s picture back into her purse. She lets out a deep sigh before calling out to her son, who had just nailed three consecutive baskets. He hugs the basketball. Christopher explains it’s Akeal’s ball. The reason why she and her son had arrived late at the park was because her son couldn’t find it at first. He refused to leave home without it.

“Every time we come to the court, he always wants to come with Akeal’s basketball,” Christopher said, looking at her youngest son. “He will never get the opportunity to do this with his brother again.”

The Impact

One Shoe At A Time: A Mother Turns Pain Into Purpose

An Unsolved Shooting Baffles a Mom for Two Decades

How Grief and Anger Turned Into Action

Silver Gun: A Robbery in Queens

Shooter: “It’s Either Them or Me”

After a Single Dad is Shot, a Community Reels