The Trash Riviera

How Dead Horse Bay and other landfills shaped New York, and the price we still pay

On sunny days, the beach glitters—literally. Shards of glass, large and small, cover Dead Horse Bay, with the occasional shoe, abandoned boat, and a tire or two. But this isn’t trash that has washed up on the shore. The beach is the trash.

And Dead Horse Bay is not the only one like that. The coastline of New York City today is vastly different from what Dutch settlers saw hundreds of years ago. Floyd Bennett Field on the southern tip of the Brooklyn coast is landfill. So is JFK airport in Queens on the northeast side of Jamaica Bay, and Battery Park in lower Manhattan, where the Hudson meets the East River. Though the trash strewn along Dead Horse Bay make its former life as a landfill more obvious, a filled-in coast is the rule rather than the exception, and New York City has filled in its edges with more than one hundred years of garbage and dredged land.

“We used to bury garbage everywhere,” says Professor Steven Cohen, the executive director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University. “And then, eventually, we put topsoil on top of it and it became real estate.”

That was the case with Jamaica Bay, which lines the southeast coast of Brooklyn, from Marine Park to East New York, and the southern part of Queens, curving around from Howard Beach to JFK airport, and protected from the Atlantic Ocean by the Rockaways. Dead Horse Bay is a small cove on the western edge of the bay in Brooklyn, and was originally a dumping ground for early 20th century New York City garbage—a pre-plastic era, hence all the glass. Today, jagged wooden pillars are all that remains of a dock where boats sailed up to unload their trash cargo.

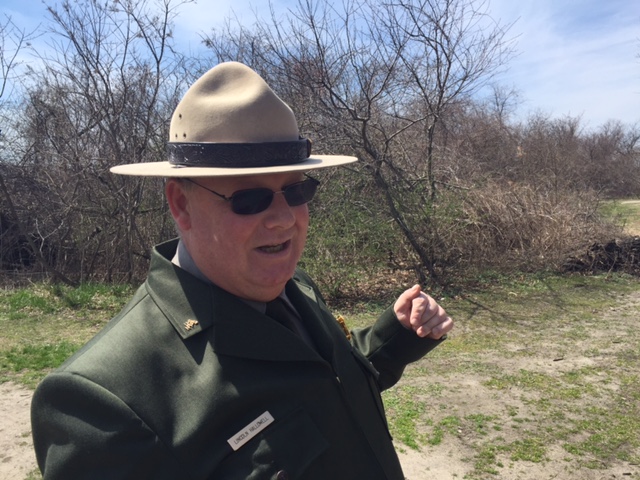

Much of the Jamaica Bay coastline was filled in from the 1920s through the 1950s. Other landfills popped up in the 1950s and 1960s, like the Fountain Avenue and the Pennsylvania Avenue landfills, just east of Canarsie. After the Fountain and Pennsylvania Avenue landfills closed, the New York Times reported that the Department of Environmental Protection invested $200 million to cover them with 33,000 trees and shrubs. In fact, converting landfills into park land is the new normal. Fresh Kills, the Staten Island landfill that closed down in 2001, is scheduled to open as a massive park in 2036. The Bronx-Pelham landfill is now part of Pelham Bay Park. And Dead Horse Bay is now part of the Gateway National Recreation Area.

But parks makeovers aside, there is a price to pay for a century of landfills, particularly landfills on the coast. Decades of aggressive filling destroyed many of the wetlands around New York City. Larry Swanson is the associate dean of the School of Marine Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook University. “One hundred and fifty years ago, those areas were considered more of a nuisance than anything else,” he says. “In part because of mosquitos, and it really wasn’t suitable for navigation. And so these lands were used as places to dispose of New York City’s waste.”

The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation says that in Jamaica Bay, 780 acres of marshland was lost between 1924 and 1974 due to dredging and filling, and 510 acres was lost due to “other reasons.” And it got worse. Between 1974 and 1999, an extra 746 acres disappeared. A report by the National Park service on Gateway National Recreation Area, which includes Dead Horse Bay, declared: “At least 95 percent of freshwater wetlands have been lost.”

Landfills are just a part—albeit a big one—of wetland problems. Others factors include pollutants like nitrogen from wastewater, and rising sea levels from global warming. And shrinking wetlands is more than just an issue for the birds and other wildlife that rely on them. Their disappearance has become a headache for humans as well.

Marshland around the city is a crucial barrier to storms, mitigating their damage. Over the past few years, New York’s once-in-a-generation hurricanes may be transforming into a more regular tradition, with devastating effects from Hurricane Irene in 2011, and Hurricane Sandy in 2012. As a result of the loss of wetlands around the city, the coast has little to no protection from the wind and water that have caused billions in damage.

“We have to be able to keep up the replenishment of the marshes and the islands at pace,” says Kate Orff, associate professor of architecture and urban design at Columbia University. “We need to make sure that the sort of islands that can support estuary life can continue.”

In the past few years, an effort to regrow wetlands around New York City has been picking up momentum. Wetlands were a part of Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s hallmark environmental strategy, known as PlaNYC. Mayor Bill De Blasio has put his own stamp on that framework, with OneNYC. In 2014, de Blasio announced $12 million for the restoration of Saw Mill Creek marsh on Staten Island. In 2014, the Department of Environmental Protection announced that the city was spending $7 million to restore over 150 acres of salt marsh islands in Jamaica Bay, and that they had secured $14 million in federal and state funding over the last 6 years. A report by the New York-New Jersey Harbor & Estuary Program and its Restoration Network Group found that since 2009, 20 wetland projects had been completed.

“Having an overarching plan is definitely a step in the right direction,” says Sean Dixon, a staff attorney at Riverkeeper. “But the devil is always in the details.” — Azure Gilman