The Trash Riviera

Dead Horse Bay is a glittering beach built of trash.

On sunny days, the beach glitters—literally.

Shards of glass, large and small, cover Dead Horse Bay, with the occasional shoe, abandoned boat, and a tire or two. But this isn’t trash that has washed up on the shore. The beach is the trash. And Dead Horse Bay is not the only one like that.

The coastline of New York City today is vastly different from what Dutch settlers saw hundreds of years ago. Floyd Bennett Field on the southern tip of the Brooklyn coast is landfill. So is JFK airport in Queens on the northeast side of Jamaica Bay, and Battery Park in lower Manhattan, where the Hudson meets the East River.

Though the trash strewn along Dead Horse Bay make its former life as a landfill more obvious, a filled-in coast is the rule rather than the exception, and New York City has filled in its edges with more than one hundred years of garbage and dredged land. “We used to bury garbage everywhere,” says Professor Steven Cohen, the Executive Director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University. “And then, eventually, we put topsoil on top of it and it became real estate.”

That was the case with Jamaica Bay, which lines the southeast coast of Brooklyn, from Marine Park to East New York, and the southern part of Queens, curving around from Howard Beach to JFK airport, and protected from the Atlantic Ocean by the Rockaways. Dead Horse Bay is a small cove on the western edge of the bay in Brooklyn, and was originally a dumping ground for early 20th century New York City garbage—a pre-plastic era, hence all the glass.

Today, jagged wooden pillars are all that remains of a dock where boats sailed up to unload their trash cargo. Much of the Jamaica Bay coastline was filled in from the 1920s through the 1950s. Other landfills popped up in the 1950s and 1960s, like the Fountain Avenue and the Pennsylvania Avenue landfills, just east of Canarsie.

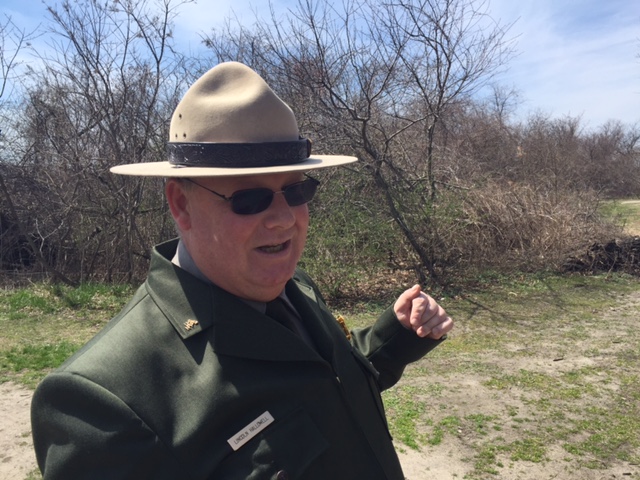

After the Fountain and Pennsylvania Avenue landfills closed, the New York Times reported that the Department of Environmental Protection invested $200 million to cover them with 33,000 trees and shrubs. In fact, converting landfills into park land is the new normal. Fresh Kills, the Staten Island landfill that closed down in 2001, is scheduled to open as a massive park in 2036. The Bronx-Pelham landfill is now part of Pelham Bay Park. And Dead Horse Bay is now part of the Gateway National Recreation Area. more >

A Cleaner Burn

NYC uses modern incinerators that turn trash into energy for homes and businesses.

New York City’s Zero waste plan is to eliminate taking trash to landfills by 2030. Waste-to-energy facilities, where trash is burned and converted into energy through incineration, currently receive less than 15 percent of the city’s trash. The leftover ash is then sent to landfills or mono-fills, special landfills just for ash. The largest waste-to-energy company in North America is Covanta, which operates 45 facilities worldwide. New York City Lens visited a Covanta facility in Hempstead, Long Island to see the processes first hand.

— Soraya Auer and Lauren Hard

Councilmember Antonio Reynoso on Waste to Energy

Chair of Sanitation and Solid Waste Management Committee

New York City's Trash Hot Spots

Marine, rail and waste transfer stations

— Jaclyn Peiser

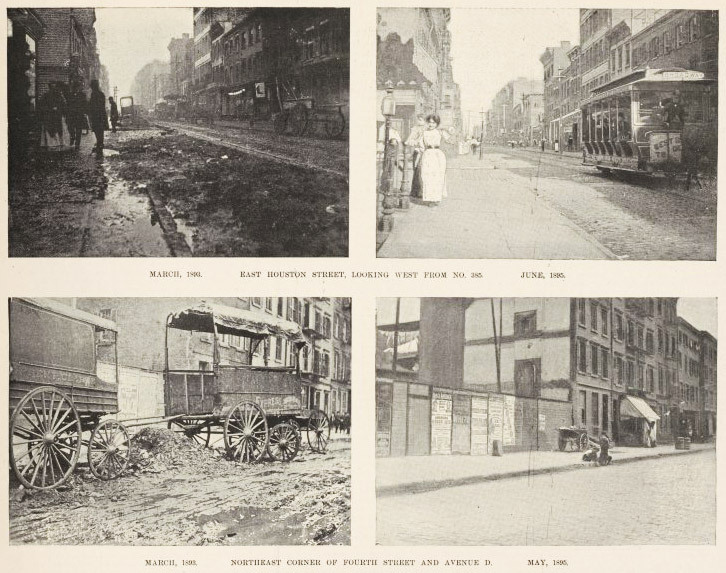

New York's Trashy Past

The city didn't even have a sanitation department until 1880. Here's a look at how New Yorkers have dealt with garbage through history.