A Cop Fires. A Boy Drops His Gun. It’s a Toy

Twenty two years later, an angry father struggles with his son's shooting

Nicholas Heyward Sr., 58, remembers the night. It was a warm Tuesday in 1994 and the sun had yet to set. Neighborhood children trickled in and out of the Gowanus Houses, the Brooklyn housing project where he lived, answering their parents’ calls, while others stayed outside to enjoy the remainder of a beautiful fall day.

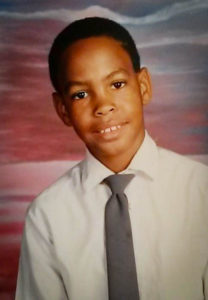

Heyward’s 13-year-old son, Nicholas Naquan Heyward Jr., was one of those few. His friends had called to him from outside to play a quick game of cops and robbers. After finishing his homework and begging permission to go out, the Nathan Hale Middle School student was ready.

The game was easy and uniformly divided: five cops and four robbers. One of the boys had gotten the toy guns from the Atlantic Antic, an annual parade that takes place on one of the adjacent streets to their homes. Throughout the evening, the boys laughed and joked as they ran throughout the 423 Baltic Street projects, including up on the building’s scenic rooftop—this was their playground.

On the ground below, a 23-year-old housing officer by the name of Brian George reported for a routine patrol.

By 3 a.m. the next morning, Heyward Jr. would be dead.

Over the last 22 years, New York City has seen 63 fake-weapon deaths. Last year, New York State attempted to do something about the problem, passing a law requiring that retailers selling toy guns make them look more like toys. And in December, New York’s Attorney General, Eric Schneiderman, described a settlement requiring fines of up to $30,000 for online retailers who sell illegal toys. The settlement follows an investigation revealing that 5,000 toy guns were sold within the state last year—most of which resembled or were replicas of deadly serious firearms, guns, pistols, and rifles. The settlement currently prevents 30 major retailers, including major chains such as Walmart, Amazon, Kmart, and Sears from selling guns that are not fluorescent, “brightly colored or have colored striping down the barrel.”

The measure could save lives—but it brings little comfort to Heyward, who believes that the appearance of his son’s toy—a small Western-style popgun with a long orange tip—didn’t make any difference.

At approximately 7:30 p.m. Officer George committed what would later be deemed by Charles Hynes, the former Brooklyn District Attorney, as a “tragic accident.” The young officer climbed the stairs of the housing project allegedly in response to a call of shots fired in one of the two housing towers.

With his finger on the trigger of the .38 caliber service revolver he carried, Officer George cautiously climbed the stairwell. Simultaneously, Heyward Jr. and the three “robbers” energetically hopped their way down the steps with their old, 18-inch, brown and black, Western carbine-styled toy guns in tow. They were ready to get the “cops” and win the game.

Heyward Jr. lead the way. When he turned the corner he saw Officer George. The two faced each other, and in that split second, each one made a life-altering decision. Heyward Jr. dropped his toy gun, according to court testimony, as Officer George shot his.

The last thing his friends heard Heyward Jr. utter was, “We’re only playing. We’re only playing,” but by the second sentence, Officer George had already shot the honors student in the stomach.

Following Nicholas’s death, Hynes described the boy’s toy as “virtually indistinguishable from a real gun,” and did not present the case to a grand jury, shocking Heyward’s friends and family. Heyward was furious.

“He lied and placed the blame on the toy gun. He had an entire table full of realistic looking toy guns to show people what Nicholas and the other boys were playing with—guns resembling those,” he said. “But that’s not what Nicholas was holding when he was shot. That gun was obviously fake.”

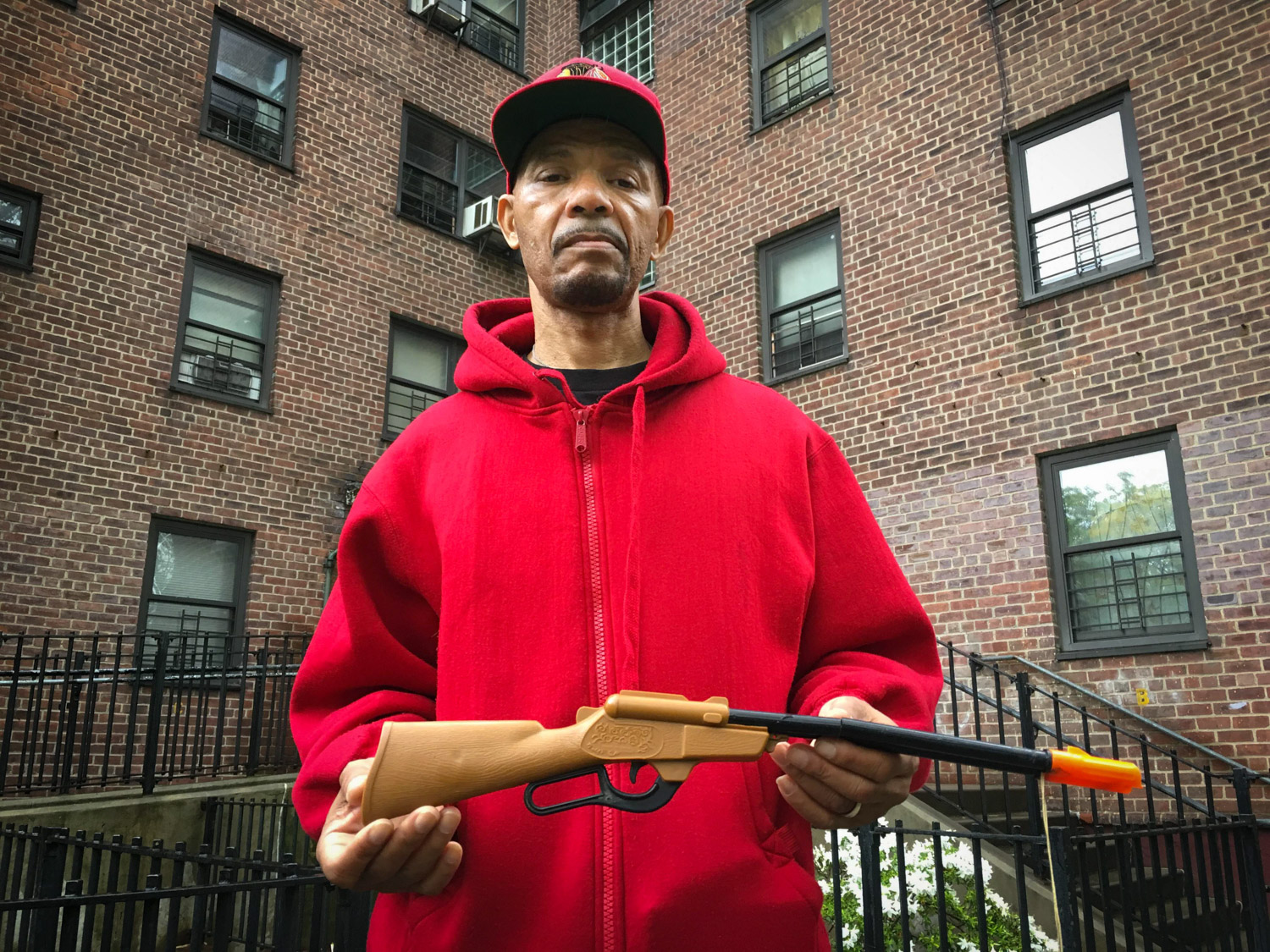

While the police collected and stored the original toy as evidence, Heyward Sr. said he purchased an identical gun—at the same Atlantic Antic festival where the original had been purchased a year later.

These days, he brings the toy with him to every gun violence protest he attends to show people how his son was killed. “Plastic toy guns are not dangerous weapons, it’s the officers,” he said. “You’re telling me trained police don’t know the difference between a toy and a real gun?”

****

At the time of his son’s shooting, Heyward Sr. was picking up his niece from her school in the Bronx. He didn’t know it yet, but Heyward Jr. was lying unconscious in a 14th floor stairwell. “My pager was ringing like crazy,” he said. “I didn’t know what was going on.”

Moments after he fired his gun, Officer George paced the neighboring hallway just outside of the stairwell door, leaving a dying Heyward Jr. alone with his three friends. Uncertain of what to do, the officer called in the incident and left in search for a local resident. According to court testimony, he then brought an elderly Hispanic woman to the scene and began to question her.

Moments after he fired his gun, Officer George paced the neighboring hallway just outside of the stairwell door, leaving a dying Heyward Jr. alone with his three friends. Uncertain of what to do, the officer called in the incident and left in search for a local resident. According to court testimony, he then brought an elderly Hispanic woman to the scene and began to question her.

“Do you know this kid?” he asked. “Can you go get his parents?”

Heyward’s then-wife, Angela, rushed to the scene minutes after eight—but she was too late. By the time she arrived, as many as eight officers were already blocking off the stairwell door, refusing her access. “She was right there and she couldn’t even touch him,” said Heyward Sr. “She was there on the 14th floor and right behind the door was her son, bleeding out and dying.”

Mrs. Heyward would be deprived of the chance to see her son twice more before his death—once on the ambulance ride to the hospital and again during his surgery at St. Vincent’s Medical Hospital.

Shortly after their son’s death, the Heywards separated, leaving Heyward Sr. in search of relief through community activism. “I help parents who’ve lost their children,” he said, “like I’ve lost mine.” He is a full-time community leader and activist for two non-profit organizations—Parents Against Police Brutality and the Nicholas Naquan Heyward Jr. Memorial Foundation. He balances his days between organizing and speaking out about gun violence around the country. When Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old boy holding a pellet gun was killed by a police officer in Cleveland in 2014, the eerily similar case struck a chord for him, 22 years after his son’s death. “I cried in front of the television when I heard that,” he said. “The fact that the officer wasn’t held accountable, and that he was only a boy with a toy…it all just reminded me of Nicholas.”

This year marks the father’s 23rd annual day of remembrance for his son. Each November, Heyward Sr. gathers alongside hundreds of community members for a day of basketball games, arts and crafts activities, and local musical performances in the Boerum Hill park across the street from his housing project. In 2001 the park was renamed Nicholas Naquan Heyward Jr. Park after his father’s push to honor his memory. In the days leading up to his death, Heyward Jr. was practicing everyday to make the basketball team at his school. He would die before hearing of his acceptance.

Every other day, Nicholas Heyward Sr. takes a stroll through the park for a reminder of what could have been.

The Impact

One Shoe At A Time: A Mother Turns Pain Into Purpose

An Unsolved Shooting Baffles a Mom for Two Decades

How Grief and Anger Turned Into Action

Silver Gun: A Robbery in Queens

Shooter: “It’s Either Them or Me”

After a Single Dad is Shot, a Community Reels